Using data to understand behaviour is crucial in PBS. As part of our work with a variety of organisations, we see lots of good practice with managers or other staff reviewing incidents and ABC information, usually close to the time in which it has been written. This is really useful for understanding aspects of what has occurred, such as:

- the detail of the contexts in which behaviours of concern might occur for someone.

- the details around the events that are triggers for the person to become unsettled or distressed.

- the approaches staff used to manage the behaviour and hopefully prevent it from escalating.

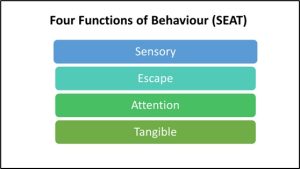

However, one of the key aims of Positive Behaviour Support is to gain an understanding of a behaviour, across incidents, so that proactive strategies can be put into place. Understanding the function of the behaviour rather than what each trigger is, helps us to put the right proactive supports into place and reduce the likelihood of the behaviour from occurring in the first place. There are four main functions of behaviour.

- Sensory, relates to sensory seeking and sensory avoiding, including physical pain,

- Escape, from people, situations, environments or tasks,

- Attention, which relates to social contact

- Tangible which includes items or activities.

By focussing on function, you can think about the different antecedents that occur during a range of incidents for someone and think about what is similar about them. This helps to consider how the person’s needs in these areas can be met proactively.

If we try to pick up these types of patterns from just reading individual incidents or ABC entries, it’s likely that we will struggle to hold all that information in our heads and make links between it all. It is very easy for memory bias or opinions to creep in, leading to the wrong conclusions being drawn. Looking at incidents in isolation from each other also means that we remain focussed on the details, which can be useful for understanding what is happening and how people respond, but not useful if we want to gain an understanding of behaviours of concern in terms of their function.

For Example:

A person might become unsettled or distressed when they see someone with a favourite food or drink on one occasion. On another occasion, the person might become unsettled when it starts to get near dinner time (because they can smell the dinner cooking).

These are two very different contexts but the function of each ‘incident’ is tangible, wanting food or drink. Looking past the details and thinking about function is essential to getting good PBS practices in place. While some services have access to PBS practitioners or specialists to help with understanding function, we know that not all do. However, regardless of the expertise and support that an organisation may have, collating objective information is essential and is a key part of Positive Behaviour Support.

Evidence as an essential part of PBS

Using evidence or objective information has been identified as an essential part of the PBS approach. The International Journal of Positive Behaviour Support paper (2022) Positive Behaviour Support in the UK: A State of the Nation Report, highlights that evidence informed decisions are a key part of the process and strategy elements that make up one of the three categories defining PBS. It’s also important to state that using data to understand behaviour is essential, but it’s also very important that we consult the person and those who know them well, enlisting their knowledge in understanding the situation and their preferences for support.

Tools to Use

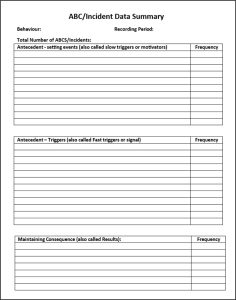

To ensure that behaviours of concern are being understood in terms of functions rather than the details, service managers, team leaders and PBS practitioners can use a variety of ways to collate the information about what happened before and what happened after the behaviour. These antecedents (before) and consequences (after) help to identify the function of the behaviour. This helps to narrow down the amount of information that you are looking at, by grouping and counting similar types of antecedents and consequences. It also helps to think about the four functions when you have done this. The image below shows a simple form for collating the information.

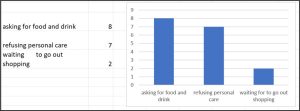

You can also collate the information using a simple excel spreadsheet and graph.

Collating this information by hand, as discussed above, can be a straight-forward way to look at the antecedents and consequences. However, if there is a lot of information or a number of different people supported, collating information by hand can become very time consuming. At Redstone, we have designed a software solution called PBS Champion, to support the ability of services to use data to understand behaviour. It provides analysis of both ABC and behavioural incident forms. These are completed electronically, and the information from them can be collated easily and very quickly, at the click of a few buttons. You can find out more information on this link https://redstonepbs.co.uk/pbs-champion/

PBS Champion

PBS Champion provides a way to analyse the detail of incidents and ABC’s with the aim of gathering information about function. However, it also provides the ability to analyse behavioural incidents and any restrictive interventions at individual, service and organisational levels. This provides a very quick and easy way to report reductions in behavioural incidents as a result supports being put into place, as well as the reduction of any restrictive interventions used, evidencing the effects of RRN standards across an organisation.

If you’re interested to find out more or arrange a free demo for PBS Champion, contact info@redstonepbs.co.uk

Author

Kate Strutt – Director of Redstone PBS and Clinical Psychologist.

Kate has over 20 years’ experience of working with adults and children with intellectual disabilities and those who are autistic, both within statutory services and the independent sector. Kate is registered with the Health and Care Professions Council. Bsc Psychology, D.Clin Psyc, MSc Applied Behaviour Analysis.